Camargue Delta

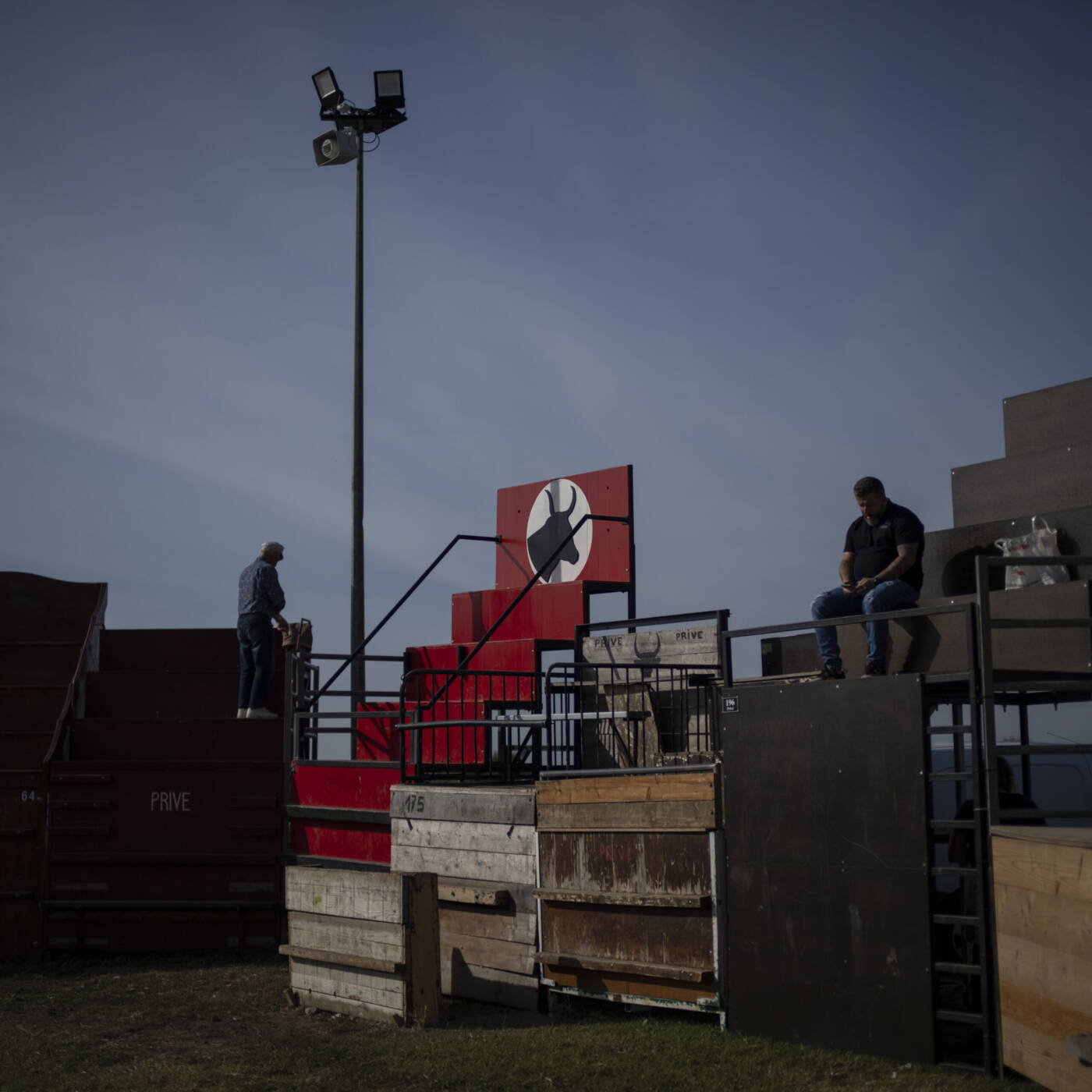

In a makeshift arena in the French coastal village Aigues-Mortes, young men in dazzling collared shirts come face-to-face with a raging bull. Surrounded by the city’s medieval walls, the men dodge and duck the animal’s charges to collective gasps from spectators. Part ritual and part spectacle, the tradition is deeply woven into the culture of the country’s southern wetlands, known as the Camargue.

For centuries people from across the region have observed Camarguaise bull festivities in the Rhone delta, where the Rhone river and the Mediterranean Sea meet. But now the tradition is under threat by rising sea levels, heat waves and droughts which are making water sources salty and lands infertile, leaving bull-herders to rethink their livelihoods.

“Here in Camargue the bull is God, like a king,” said Aigues-Mortes resident Jean-Pierre Grimaldi as he cheered on from the private arena stands, where he’s watched competitions for decades. “We live to serve these animals … some of the most brilliant bulls even have their own tombs built for them to be buried in.”

Generations of “manadiers” or ranchers, like Frederic Raynaud in the Camargue just east of Aigues-Mortes, have dedicated their lives to raising the bulls that are indigenous to the region. Wilder bulls that can win prestigious fighting events are the most prized.

Raynaud, a fifth generation manadier, has raised many such bulls on his “manade,” a term for ranches in the region. His ranch currently looks after around 250 Camargue bulls and 15 horses in semi-wild pastures along the coast. But he fears that soon his much-celebrated cattle will not have lands to graze on.

“The sea level rises on our coast and takes more and more of our land”, Raynaud said.

A temporary dyke constructed by local authorities to stop the growing sea has sunk in on itself, the water passing right through it and into the manade’s pastures. The edge of the ranch is slipping into the sea. Land that hasn’t been swallowed by the water is becoming unusable as encroaching seas make the wetlands increasingly salty. Heat waves and drought, exacerbated by climate change, are also depriving the land of fresh water, allowing sea water to take over.

“We used to have the salt rising up on just on our land nearer the coast”, Raynaud said. “But now the salt rises up through the soil five or six kilometers (three to four miles) beyond the shoreline where you can see salt encrusting over the vegetation.”

The sea level around the town of Saintes-Marie de la Mer in Camargue has risen by a steady 3.7 millimeters (0.15 inches) per year from 2001 to 2019, almost twice the global average sea level rise measured throughout the 20th century, according to the local Tour du Valat research institute. Warming, expanding oceans and the melting of ice over land, both a result of climate change, are contributing to higher sea levels.

Researchers added that the advance of salt up into the soil would leave the land barren and uninhabitable long before the sea engulfs it. Some affected pastures have already become bare with little vegetation available for animals to graze and the abnormally high salt content poses health risks to organisms not able to tolerate it.

People have always been attracted to the Camargue because of the abundance of species and resources it contains despite the challenges of living between the ebb and flow of an ever-evolving delta. Its nutrient-rich wetlands sustain an enormous amount of biodiversity, making it one of the most productive ecosystems in the world.

The Rhone river has long served as the Camargue’s lifeline bringing fresh water from the Alps and dampening salt levels in the Camargue. As rain and snowfall decrease, it’s becoming a less reliable fresh water source, with researchers estimating that the river’s flow has reduced by 30% in the last 50 years and is expected to only worsen.

“Glaciers which are in the process of melting at an incredibly high rate have already passed the point of no return, so probably in the years to come, the 40% of river flow that arrives in Camarague will be reduced to a much smaller percentage,” said Jean Jalbert of the Tour du Valat research center.

In summers plagued by high temperatures and diminished rainfall the sea water can rise up to twenty kilometers into the Rhone river. During a heat wave in August this year, the Raynaud family’s water pump in the Petite Rhone, an offshoot of the main river, began pumping salt water. They were forced to move their pump farther up the river outside the perimeters of their own ranch to irrigate their land and feed their animals.

The Raynauds recently bought 10 hectares of land further north to be able to graze their bulls.

“It isn’t that much for 250 bulls but if one day there’s a catastrophe, that will be a fall back if we ever are forced to start again somewhere new,” Raynaud said.

Manadier Jean-Claude Groul already grazes his animals across separated pastures, taking advantage of the different conditions each offers for his cattle. At the crack of dawn, he whistles as he walks through an open field until a group of cotton-white Camargue horses heed his call and emerge from the fog. Groul loads his horses onto his truck and drives from one of his pastures to another he owns farther down the road.

“One day if things get worse, we will have to find land further north” he said.

Less and less territory is being prioritized for the ranches as authorities scramble to acquire land destined for preservation. Christine Aillet, the mayor of Saintes-Maries de la Mer, pointed that statewide preservation efforts are putting nature over her townspeople.

“They tell you on TV that the Camargue needs to be renaturalized,” said Aillet, who is skeptical of schemes aimed at saving the region by limiting global warming and reforesting the land. “If we renaturalize … the Camargue will leave us dry without fresh water,” she argued.

Aillet is in favor of measures such as increasing the number of tidal barriers along the coastline which she says will help residents, but researchers say these ideas are only a temporary fix and won’t withstand the affects of coastal erosion a fast-altering climate.

Scientists in the region say that the Camarague risks losing both its economic and cultural worth as well as its natural beauty if interventions aren’t taken to help curb climate change. Top climate experts around the world say sea levels will continue to rise and that drastic action is needed to stop making the problem worse.

“For the past five generations the Camarguaise lived with the belief that the balance of Camargue is and forever will be stable, but we are in a delta that is beginning to face climate change,” said Tour du Valat’s Jalbert. “This ecosystem, that we believed to be stable, is starting to show cracks.”

For Frederic Raynaud, how big those cracks get will determine whether he’ll be able to maintain a ranch that has been in his family for over a century.

“I’ve always been here, grown up here, the animals have always been here,” he said. “Leaving this place would be awful but if one day the sea arrives here, we will have to go.”

AuthorDaniel ColeYear2022LocationFrance

Manadier Jean-Claude Groul’s hat sits on the dashboard of his truck as he transports Camargue bulls from one pasture to another. Due to the evolving realestate market and environmental factors, manadiers like Groul are having to breed their animals higher up at the limit of the Camargue Delta, often fracturing their land and forcing them to transport their animals in trucks across separated pastures. Camargue, October 2022. Daniel Cole.

Hoofprints left by Camargue bulls mark a section of pasture encrusted with salt on the Manade Raynaud in Camargue. As soil salinity rises due to drought and a reduced riverflow from the Rhone river, the land traditionally used by bullbreeders like the Raynaud family is becoming more and more difficult to maintain as a suitable pace to raise animals. Camargue, September 2022. Daniel Cole.

A dyke built to hold back the sea from advancing into the Manade Raynaud pasture is pictured in Camargue. The dyke was created by local authorities as a temporary solution but is pushed farther back each year. ÒIt is impossible to stop the sea, maybe we can slow down its rise, but we cannot stop it. She does what she wantsÓ says Frederic Raynaud. Camargue, September 2022. Daniel Cole.

A man adornes a statue of Saint Sara with jewlery in the church of Saintes-Maries de la Mer in southern France. As the saint of Saintes-Maries de la Mer and legendary role as servant to one of the Three Marys who made landfall in Camargue, Saint Sara is venerated throughout Camarguaise folklore and tradtion. Camargue, September 2022. Daniel Cole.

The tomb of a celebrated Camargue bull named Regisseur is pictured at the Manade Raynaud in Camargue. Bulls with distinguished characters and repeated successes in the course camaguaise competitions are celebrated as legends throughout the region long after their passing. Camargue, October 2022. Daniel Cole.

Manadier Jean-Claude Groul operates an irrigation pump on the Mande Saint-Louis in Camargue. Like all the Manadiers in the region, Groul must irrigate his pastures with fresh water from the Rhone river in order to keep the vegetation healthy and the soil salinity at a sustainable level. Camargue, September 2022. Daniel Cole.

Stocks of hay stored for the winter months to come are pictured in a silo at the Manade Saint-Louis in Camargue. When pastures in Camargue fail to naturally produce enough vegetation to feed the animals, manadiers must import additional reserves of animal fodder to feed their animals. Camargue, October 2022. Daniel Cole.