Eroding Franco

‘Eroding Franco’ is a photography project that relates Franco’s regime’s environmental debt (1939-1975) to Spain’s current desertification crisis.

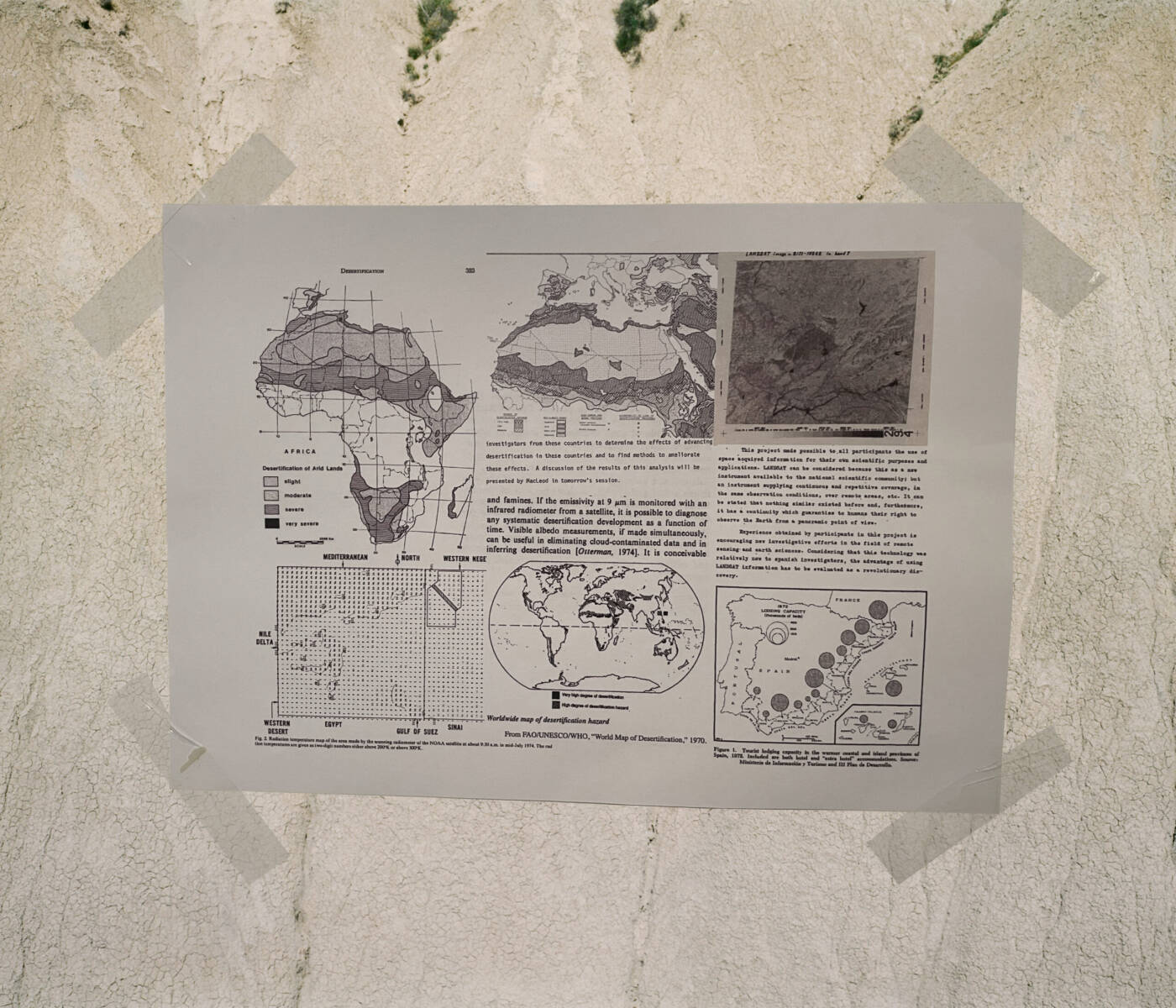

Desertification, the transformation of fertile territories into barren landscapes, is a critical global challenge intensified by unsustainable practices such as poor water management or harmful agricultural methods. While this environmental challenge spans continents, its imprint is deeply felt in Spain.

The legacy of Francoism goes beyond social and political repression. The regime’s decisions over 36 years, fostered a culture of destruction and neglect for the land, prioritizing economic growth.

The regime cemented mass tourism, agro-industry, and construction as the ‘economic pillars’ of Spain, setting the stage for the country’s future. These ‘economic pillars’, comprising around 30% of Spain’s economy today, were heavily promoted in the 1960s and 70s, an era referred to as the “Spanish economic miracle” (1959-1974) that established the transformation of Spain into a ‘desertification machine’.

According to scientific reports from the Spanish Ministry of Environment, Spain is on a trajectory where, by the end of the 21st century, 80% of its territory may face critical desertification. Yet, this phenomenon is not merely an environmental crisis; it is a transformative force that destabilizes rural economies, displaces communities, and fractures the cultural and historical ties that have long defined Spain’s relationship with its land. It reveals the interconnectedness of ecological degradation, economic marginalization, and the erosion of collective social memory.

During Franco’s era, some scientists studied Spain’s environmental trajectory and potential consequences. However, the regime, possibly without fully understanding these implications, prioritized other aspects of development and economic growth. This lack of awareness set Spain on a path that would pose significant environmental challenges for future generations.

The synergy between historical information and contemporary photography is at the heart of ‘Eroding Franco.’ It delves into the key factors of Spain’s desertification—mass tourism, construction, and agroindustry—and intertwines archival research with documentary photography, offering a comprehensive but distinct perspective of how past decisions shape present realities.

Alongside the historical legacies, Spain’s desertification crisis is exacerbated by contemporary climatic factors such as torrential rains and wildfires. These events are often caused and worsened by human actions in the context of climate change, stripping away fertile land and leaving behind poverty, especially in rural areas. As fields turn barren, farmers struggle, highlighting a direct link between environmental damage and economic hardship. This aspect of the story shows the ongoing effects of past decisions on today’s communities, adding a crucial layer to our understanding of Spain’s environmental and social landscape.

‘Eroding Franco’ seeks to expand photographic boundaries by incorporating scientific insights, offering a fresh perspective on the human-environment narrative. The project challenges conventional thinking and immerses audiences in the realities of climate change. In essence, ‘Eroding Franco’ underscores the importance of understanding our past to address today’s pressing environmental challenges.

This project is made possible with support from the National Geographic Society, The Royal Photographic Society, and Photographic Social Vision.

AuthorJordi Jon PardoYear2024LocationSpainStatusWork in progress

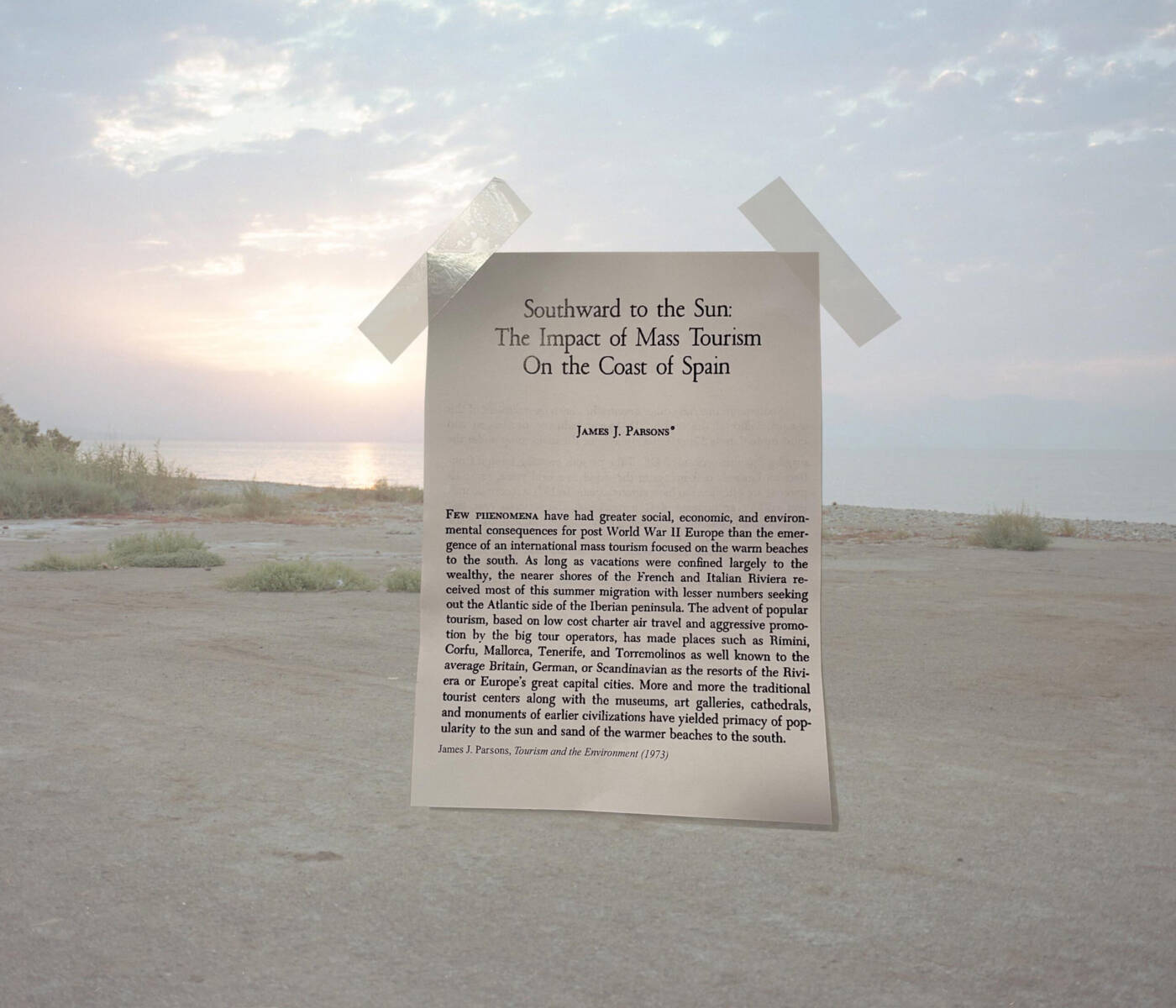

Archive: 'Tourism and the Environment' by James. J. Parsons, 1973.

Background: El Cabo Cope, a largely virgin enclave of the Mediterranean coast, stands as one of the last bastions against mass tourism, a development that has transformed much of Spain's Mediterranean coastline. Calnegre, November 2019.

As the sun dips beyond the horizon, tourists gather to soak in the captivating spectacle of Benidorm. Once a humble fishing village, the city was radically transformed during Franco’s regime with a vision of establishing a coastal tourism hub. Decades later, it stands as Spain’s major epicenter for mass tourism. However, a crucial environmental concern emerges beneath the allure of beaches and vibrant nightlife. According to the Spanish Forum of the Economy of Water, a typical tourist in Spain reportedly uses three to four times more water than a resident, approximating 300-400 liters per day. This highlights the significant environmental strain the burgeoning tourism industry imposes on Spain’s natural resources, raising important considerations for sustainable development. Benidorm, June 2022.

A souvenir from Benidorm offers a tangible representation of the marine ecosystem. Since Francoism, the city's booming tourist industry has reshaped the landscape, compressing dunes into beaches and replacing natural coastlines with concrete. As recent studies have revealed, such urban developments have led to habitat loss and a decrease in biodiversity, challenging the survival of native marine life. In the broader context of climate change, with rising sea levels and changing weather patterns forecasted to alter coastal landscapes, Benidorm's commitment to enhancing coastal resilience becomes crucial. Benidorm, October 2022.

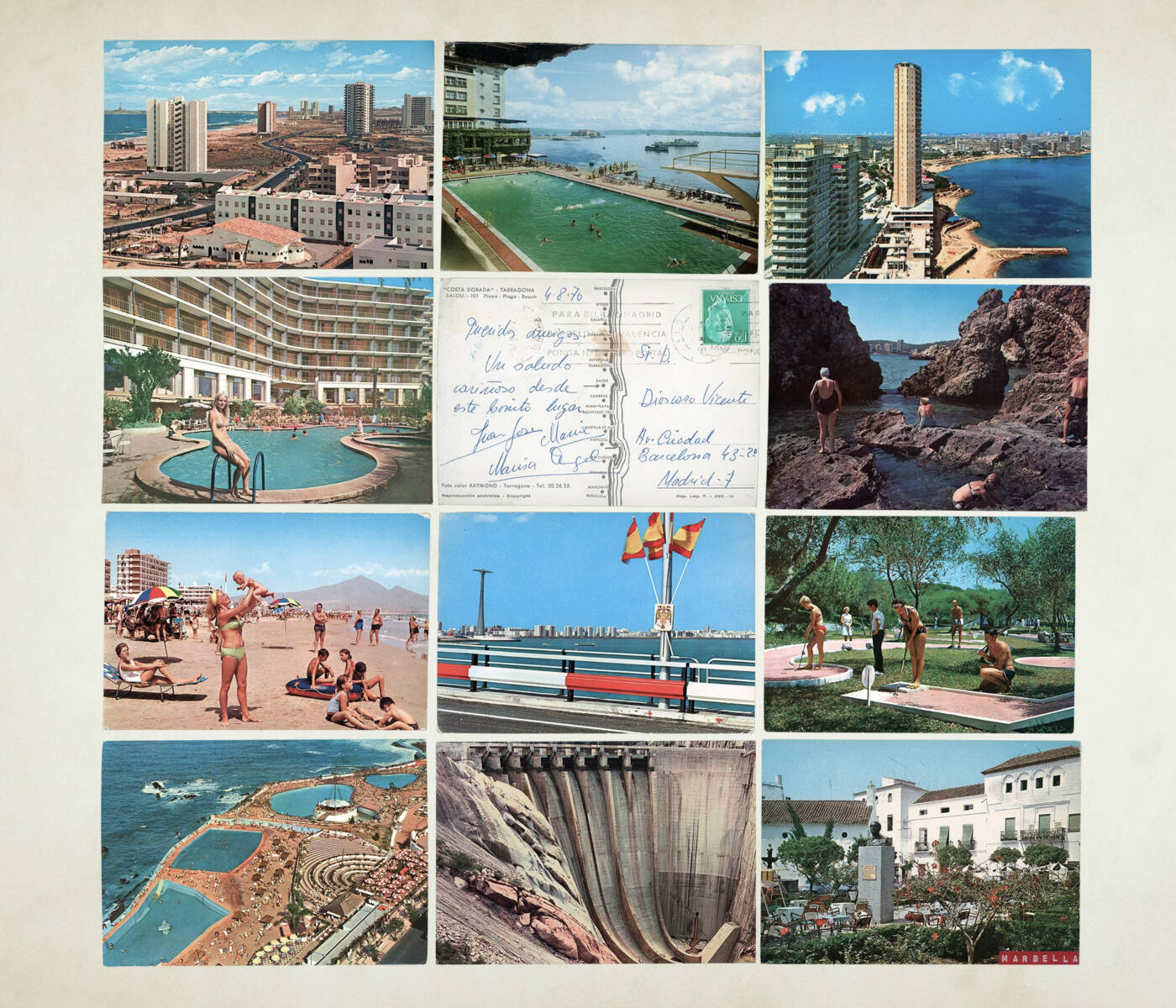

Reflecting on the historical transformation of Spain during the late 1960s and '70s, this collection of postcards captures the dawn of mass tourism and the ushering in of an era driven by technical governance and economic expansion. Time capsules to a moment when Spain was on the cusp of change, evolving from post-war isolation towards global exposure. Yet, beyond their sun-soaked facades lies the inception of an environmental trajectory that resonates profoundly with Spain's contemporary landscape challenges. Spain, April 2024.

Tabernas, once the cinematic playground for spaghetti westerns, now hosts a unique theme park. The dusty lanes and weather-beaten structures that once acted as backdrops for dramatic duels and horse chases are now populated with visitors, each relishing their chance to step into a live-action western narrative. Beyond its entertainment value, Tabernas holds a more profound, somewhat chilling relevance. Situated in the heart of the desert, it is a potential precursor for the country's environmental future. As Spain grapples with escalating desertification, Tabernas may offer an early glimpse of the landscape that could define the nation by 2100. Tabernas, June 2021.

Swimming pools within tourist apartments in Torrevieja, a town in the water-stressed southeastern corner of the Iberian Peninsula. Spain’s paradox and status as one of the countries with the highest number of swimming pools per capita worldwide, with one pool per 35 inhabitants, despite its growing desertification and acute water scarcity. This scenario is more than an ironic contrast but a confrontation of the intricate relationship between water management, tourism, and environmental conservation. The prevalence of swimming pools, primarily driven by the demands of mass tourism, signifies an uneasy imbalance when facing an escalating water crisis. Herein lies a tension between economic pursuits and environmental sustainability, where abundant water, a life-sustaining resource, is used liberally for widespread recreational purposes. While catering to tourism's temporary needs, this usage inadvertently perpetuates the cycle of desertification, a major outcome of which is further water scarcity. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle, where attempts to alleviate one issue inadvertently exacerbate another. Torrevieja, July 2023.

Archive: 'Soil Erosion in Spain' by Hugh Hammond, 1960.

Background: The impact of "La Gota Fría": In the aftermath of torrential rains, the municipal pavilion in Benferri was blanketed in mud. This severe weather phenomenon, commonly striking numerous Mediterranean communities towards summer's end, left a trail of destruction in its wake. When intense rainfall occurs, the soil's capacity to absorb water is overwhelmed, leading to runoff. This runoff carries topsoil, organic matter, and nutrients away, degrading the land's fertility and structure. Benferri, September 2019.

Every evening, a regular football match unfolds in the Almanzora River. It’s a shared ritual for the young people. Their vitality contrasts the arid surroundings shaped by relentless climate shifts and human actions. Here, the Almanzora River stands as a shadow of its former self. Once a thriving waterway, it has been reduced to an almost dry riverbed by persistent droughts and local agricultural practices. In this environment of scarcity, the residents' everyday lives and leisure activities persist, creating a juxtaposition between human tales and environmental crises. Cuevas del Almanzora, August 2020.

A reflection of the Christ of Monteagudo, initially erected in 1926 atop a historically Islamic castle, was commissioned by the Church during Primo de Rivera's dictatorship as a symbol of Christian supremacy and met its demise during the Spanish Civil War, torn down by Republican forces. The act was emblematic of the broader secular and anti-clerical sentiments that marked the Republican side, reflecting their opposition to the Church’s alignment with the Nationalists. After the war, during Franco's time, seizing the symbolic and ideological power of the statue, ordered its reconstruction in 1951. A calculated assertion of his regime's commitment to re-establishing and centralizing Catholic values as a cornerstone of his authoritarian rule, intertwining the narrative of religious revival with the narrative of national recovery under Francoism. A sentinel etched against the sky, the silent narrative of the Southeast reveals itself—a portrait woven with threads of fervent belief and the former reality of nature's plight. And despite its contentious past, the Christ of Monteagudo remains a tourist attraction in the Southeast. Monteagudo, April 2024.

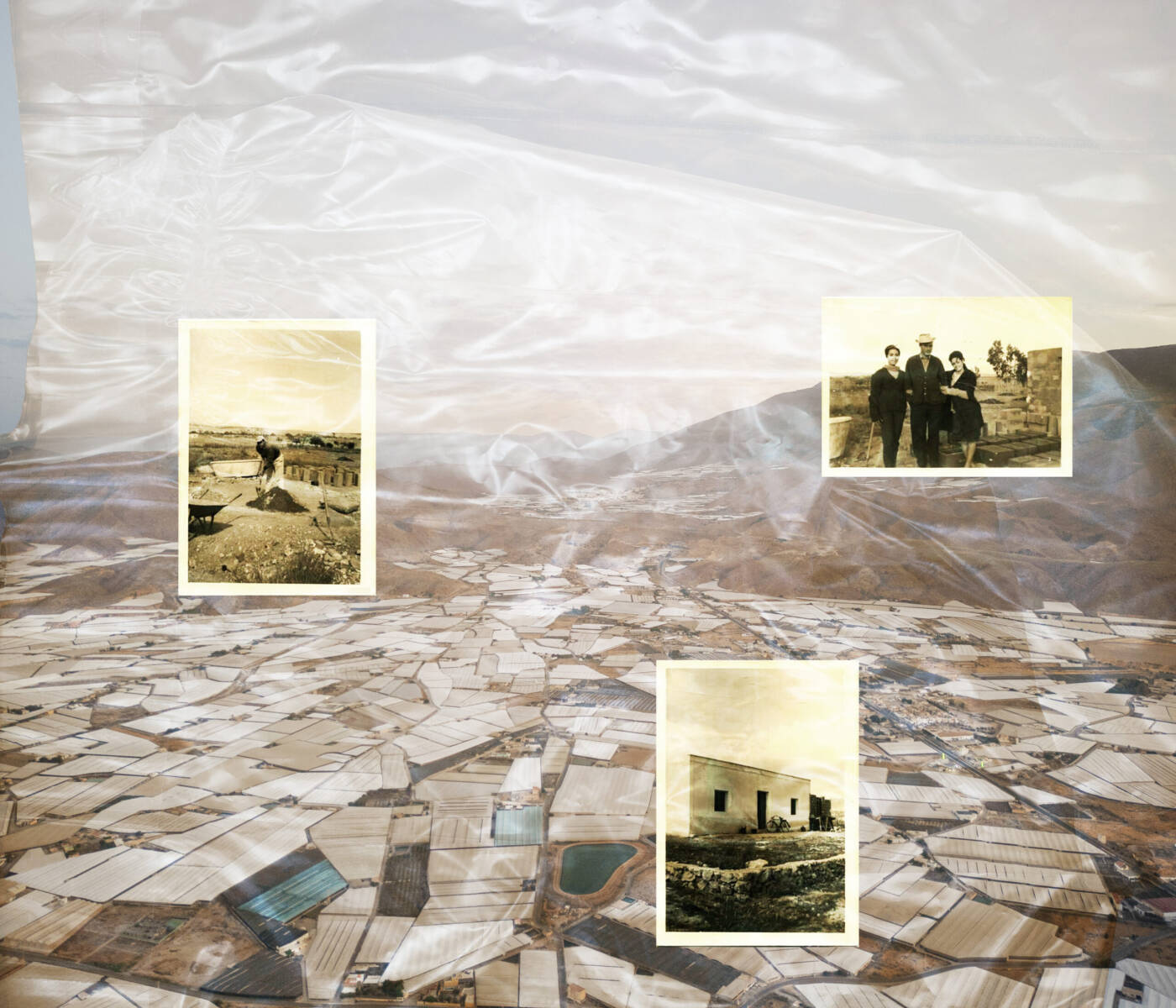

Fields of greenhouses ripple across the Southeast, creating the "Mar de Plástico" or "Sea of Plastic" in the province of Almería. Concealed behind the gates of Adra, these hectares of greenhouses mask an underlying reality of lands affected by waste pollution and chemical residues. The birth of this agro-industrial expanse dates back to the 1960s, during Franco’s period of autarky. Fast forward to nearly six decades later, this corner of Southern Spain has morphed into the largest conglomeration of greenhouses in the world. The relentless spread of these greenhouses has now claimed more than 30.000 hectares of Mediterranean nature. Adra, July 2021.

In 1964, these photographs captured a landscape in transition: rudimentary tools, open horizons, and people shaping the land with their hands. Today, those memories hover over the same place, now veiled in layers of polyethylene—discarded, weathered, found here in Almería's "Mar de Plástico." In the Southeast, the balance between humans and the earth has given way to industrial food production, erasing the connection between people and nature. El Ejido, July 2024.

The whitewashing of a greenhouse in the "Mar de Plástico." This process is crucial for controlling the temperature inside the greenhouse by reflecting a portion of solar radiation, protecting crops from excessive heat. It is essential for maintaining efficiency and productivity in the world's largest greenhouse complex. The Southeast relies heavily on a diverse workforce, including many migrant workers contributing significantly to the Agribusiness Cluster in Almería. Their efforts help sustain the area's agricultural output, bringing economic growth to the region while presenting environmental and social challenges. Whitewashing greenhouses typically occurs in the second half of July each year. Workers in the "Mar de Plástico" frequently endure harsh conditions under the intense sun. Vícar, July 2024.

Six dead pine saplings were collected in September 2024, nearly a year after La Junta de Castilla y León's replanting efforts following the devastating wildfire in the Sierra de la Paramera in August 2021. The historical practice of planting pine monocultures in Spain dates back to the 1940s as part of a post-war economic recovery strategy. Large-scale reforestation with species like Pinus pinaster and Pinus sylvestris occurred, especially in regions like Castilla y León. While initially aimed at economic recovery, these monocultures have also contributed to increased desertification risks over the years. Veteran forest rangers, who once helped replant these areas, now find themselves overseeing the same forests they once cultivated, this time managing burned timber exploitation and new pine reforestation attempts. However, the continuing efforts to plant pines, as seen in late 2023, often face the same problems. The fragile, dying saplings highlight the ecosystem's resistance to monoculture reforestation, particularly in regions already devastated by fire. The proximity of pines in these monocultures promotes the spread of fires due to their high flammability. This exacerbates wildfire risks and diminishes biodiversity, making ecosystems more fragile and less resilient to future disturbances. Sierra de la Paramera, October 2024.

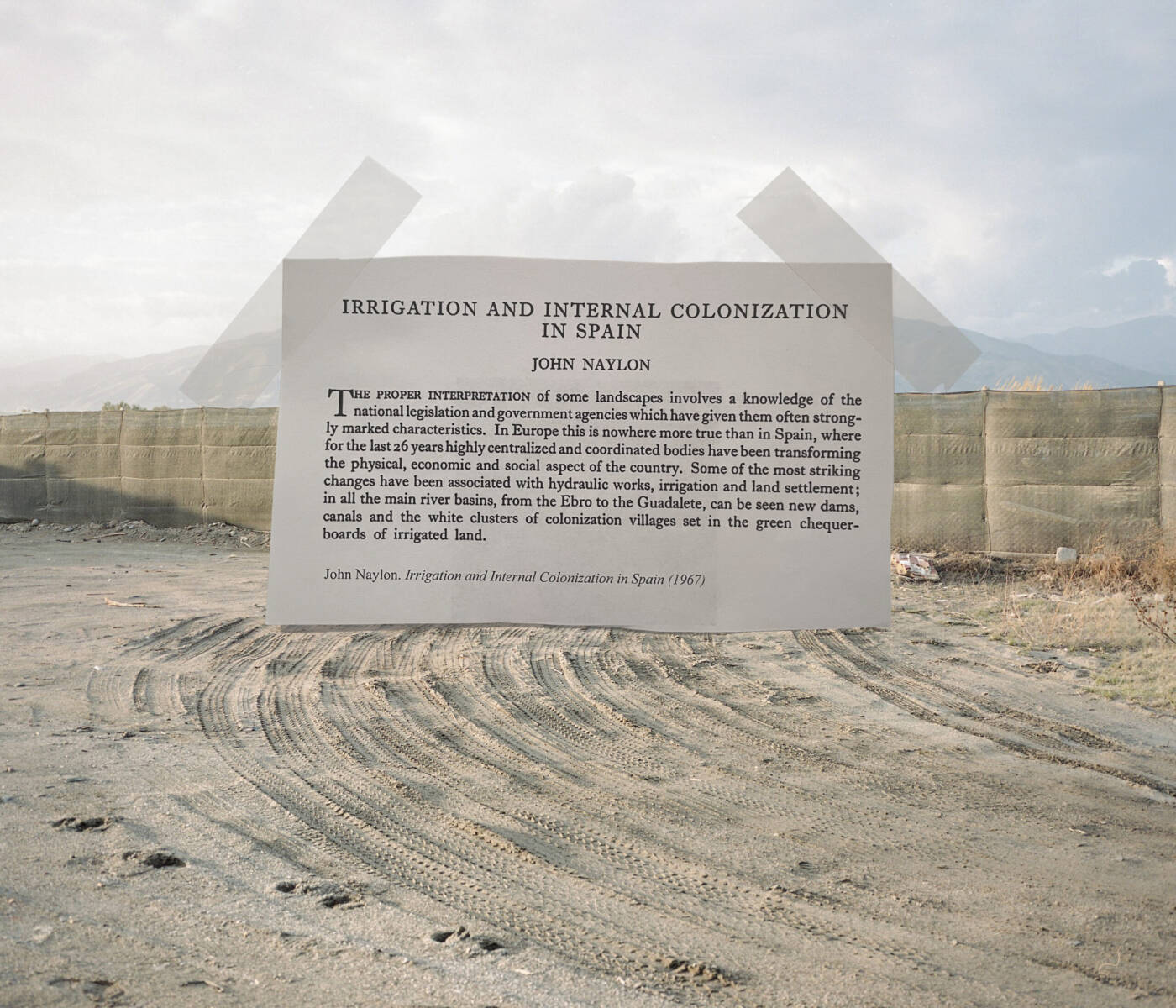

Archive: 'Irrigation and Internal Colonization in Spain' by John Naylon, 1967.

Background: A fence lines the edge of a greenhouse in the "Mar de Plástico," where endless rows of polytunnel greenhouses dominate the landscape, another road to the intensive agro-industry thriving in the region, the world’s largest greenhouse complex. Adra, November 2019.

The Church of Mediano stands as a ruin of Spain’s dam-building legacy. During the Franco era, an ambitious water policy led to a proliferation of these structures nationwide. This period saw tension between visions of how and for what purpose water should be used: to power the growing electrical demands of a modernizing Spain or to nourish fields and sustain agriculture? Dams and reservoirs became symbols of progress and modernity, grandly inaugurated by the regime. Yet, behind these massive hydraulic structures lie stories of displacement, of submerged towns like Mediano, and lives forever altered. Spain’s water reservoirs, currently accounting for the most prominent dams in the European Union, are a testament to these complex narratives of progress, displacement, and ecological considerations. In the photograph, the Church of Mediano, built in the XVI century and normally inundated, emerges entirely from the water. The village of Mediano was flooded in 1969, and now, particularly during times of drought, the church’s appearance prompts reflections on the balance between human ambition and nature’s resilience. Mediano, August 2023.

The Church of Mediano stands as a ruin of Spain’s dam-building legacy. During the Franco era, an ambitious water policy led to a proliferation of these structures nationwide. This period saw tension between visions of how and for what purpose water should be used: to power the growing electrical demands of a modernizing Spain or to nourish fields and sustain agriculture? Dams and reservoirs became symbols of progress and modernity, grandly inaugurated by the regime. Yet, behind these massive hydraulic structures lie stories of displacement, of submerged towns like Mediano, and lives forever altered. Spain’s water reservoirs, currently accounting for the most prominent dams in the European Union, are a testament to these complex narratives of progress, displacement, and ecological considerations. In the photograph, the Church of Mediano, built in the XVI century and normally inundated, emerges entirely from the water. The village of Mediano was flooded in 1969, and now, particularly during times of drought, the church’s appearance prompts reflections on the balance between human ambition and nature’s resilience. Mediano, August 2023.

After a rare rainfall, the Rambla de Albox, a tributary of the Almanzora River, briefly reclaims its role as a waterway in southeastern Spain, hosting transient pools that reflect the fleeting clouds above. For most of the year, however, its dry riverbed underscores the challenges of water scarcity that confront a region increasingly affected by drought and intensified urban development. Albox, May 2024.

In these glass jars lies a small catalog of what still survives—creatures taken from their natural world to rest eternally in alcohol. The ladder snake, the Iberian midwife toad, the Spanish terrapin, and the Iberian newt are remnants of a transformed landscape of forests and rivers that gave way to roads, hotels, developments, and the mere expansion of a dead land. Their habitats, stripped to feed the appetite for relentless expansion, fade from the map of a Spain that reinvents itself at the cost of what was once shared life. This row of jars marks the trace of a sacrifice: the price of progress, which continues to write, unceasingly, the story of what we have lost. Madrid, September 2024.

Naseem, a ten-year resident in Albox, and Imran, who has newly arrived from Islamabad, discuss life's challenges far from their homeland. Behind them, a faded sign depicts a real estate project that never materialized, unfulfilled ambitions during Spain's economic crisis. As Imran learns Spanish and adapts to his new surroundings, the surrounding landscape, marked by unused plots and modern ruins, underscores the region's unrealized economic potential. Albox, May 2024.

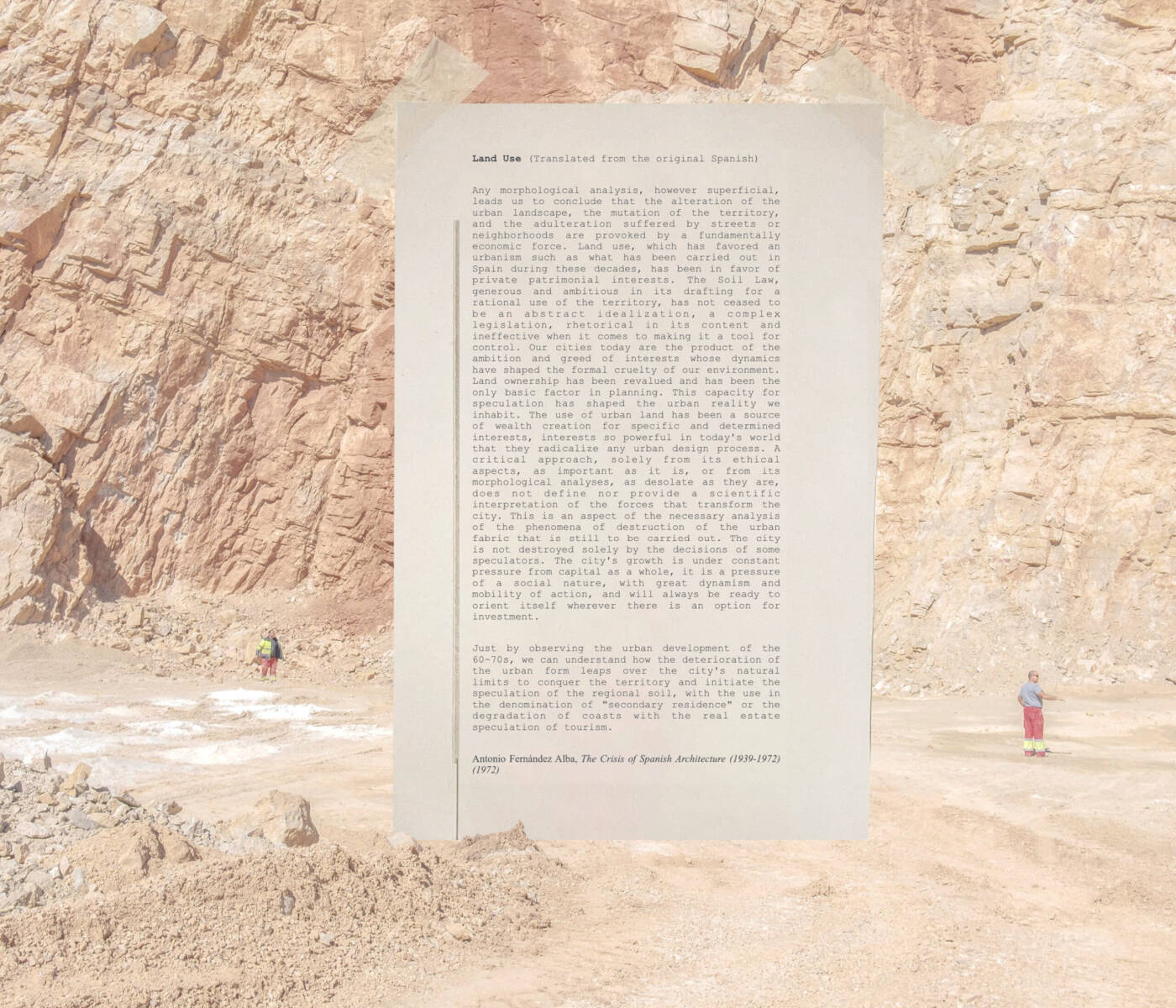

Archive: 'The Crisis of Spanish Architecture (1939-1972)' by Antonio Fernández Alba, 1972.

Background: Over four decades, the Alcover Quarry in Tarragona has meticulously harvested limestone, a testament to the enduring balance between industrial progress and the Spanish landscape's integrity. Its materials contribute to civil works, honoring a tradition that melds the natural with the built environment. Alcover, May 2021.

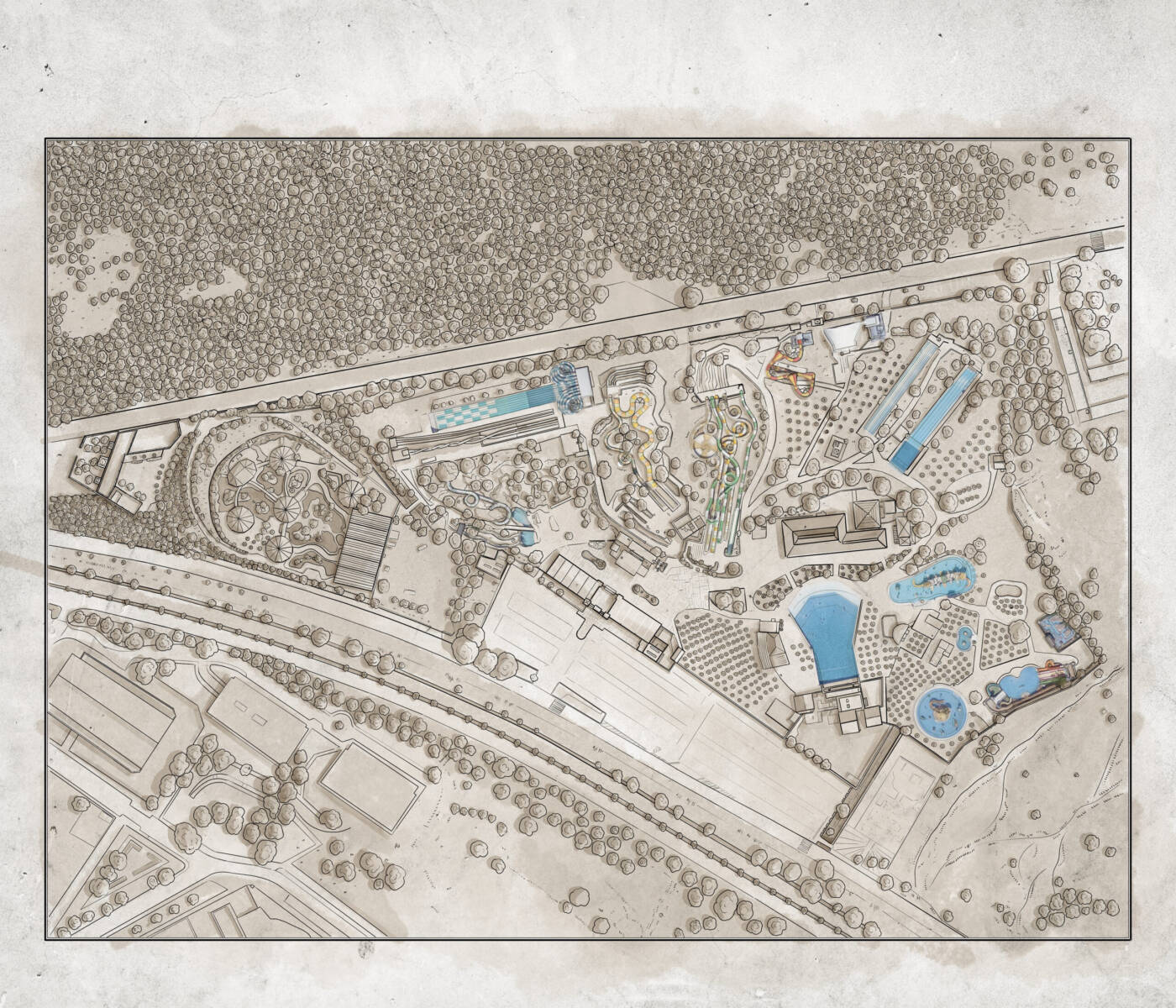

From chains to waterslides: What was once a Francoist concentration camp is now Aqualand, a water park where memories drown in oblivion. This area of Torremolinos, transformed from a site of repression into a space of leisure, reflects a collective amnesia about Spain’s dark past and the shift towards mass tourism that emerged during the Spanish “economic miracle.” In Málaga, a similar transformation occurred just 5.84 km northwest of Aqualand. The Málaga airport was merely a military base during the Spanish Civil War. Still, it began its transition into a civilian airport through the forced labor of prisoners from the Torremolinos concentration camp. Working under inhumane conditions, these individuals contributed to constructing a civilian passenger terminal starting in 1938. While initial works began during the war, the expansion was not completed until a decade later. This development laid the groundwork for the airport’s modernization in the 1950s and 1960s, allowing it to welcome international tourists as part of Franco’s strategy to boost the economy and improve Spain’s global image. The expansion reflects the era’s focus on modernization, often achieved through harsh measures and forced labor. Today, Málaga Airport symbolizes the region’s transformation through tourism, much like the Torremolinos camp repurposed as a leisure center. Photograph by Jordi Jon. Cartographic interpretation by Pablo Uría. Torremolinos, May 2024.

Background: The football field in Beas de Granada stands out for its grayish-white surface, covered with local aggregates extracted from the nearby Triturados Puerto Blanco quarry, which has been active since the 1960s. The surrounding mountains, which sustain the village in practical ways, also carry the weight of history. During the grim years of the Spanish Civil War, these hills bore witness to countless executions, including that of poet Federico García Lorca. Beas de Granada, May 2024. Above: Embedded within ‘Eroding Franco’ is an exploration of the daily transformation of our environment to serve human activities. This global phenomenon sits at the intersection of economic growth and ecological sustainability. At the heart of this inquiry lies Òdena, Barcelona, home to a significant metal foundry. Here, raw materials from extensive mining activities are shaped into essential components for daily life and industrial machinery. ‘Eroding Franco’ captures these intersections of history, human action, and environmental resilience. Òdena, March 2021. Below: In inner Almería, the world's largest marble quarry stretches like a white scar across the landscape, reflecting centuries of resource extraction in service of what we call civilization. Declared public property in 1947, it expanded under Franco's autarkic policies of the 1940s and 50s, prioritizing intensive resource exploitation for national reconstruction. This marble, shaping monuments from Roman times to the Alhambra, gained unprecedented demand during the 1960s' "economic miracle". Today, the quarry stands as an ever-growing mark of humanity’s relentless drive to build, leaving behind a profound and enduring toll on the natural world. Macael, May 2024.

In the stillness of an empty laboratory, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic remained. This photo, taken in February 2021, captures Sener Aeroespacial, a leading Spanish aerospace research and engineering company. Their work focuses on the environmental impacts of human activity, particularly the advancing desertification in the Iberian Peninsula. In November 2020, a mistake caused a devastating trajectory deviation of a rocket carrying Spain’s SeoSat-Ingenio and France’s Taranis, resulting in the loss of a decade-long €200 million project to monitor European climate changes. Despite this setback, the company's dedication to sustainable practices remains steadfast. Barcelona, February 2021.

Mass tourism under the night sky in Costa de la Calma. Empty loungers surround a quiet pool, waiting for the next wave of tourists, even in October—Mallorca’s so-called low season, when daytime temperatures still hover around 25 degrees Celsius. The island sits at the core of Spain’s tourism machine—a transformation that began in the bright days of the milagro económico (1959-1973). Since then, year after year, waves of visitors have placed increasing pressure on Mallorca’s water reserves, pushing the island closer to drought and accelerating erosion. Also, another way of desertification: one that leaves Mallorca’s towns and villages hollowed out, giving way to tourists and seasonal residents. Costa de la Calma, October 2024.

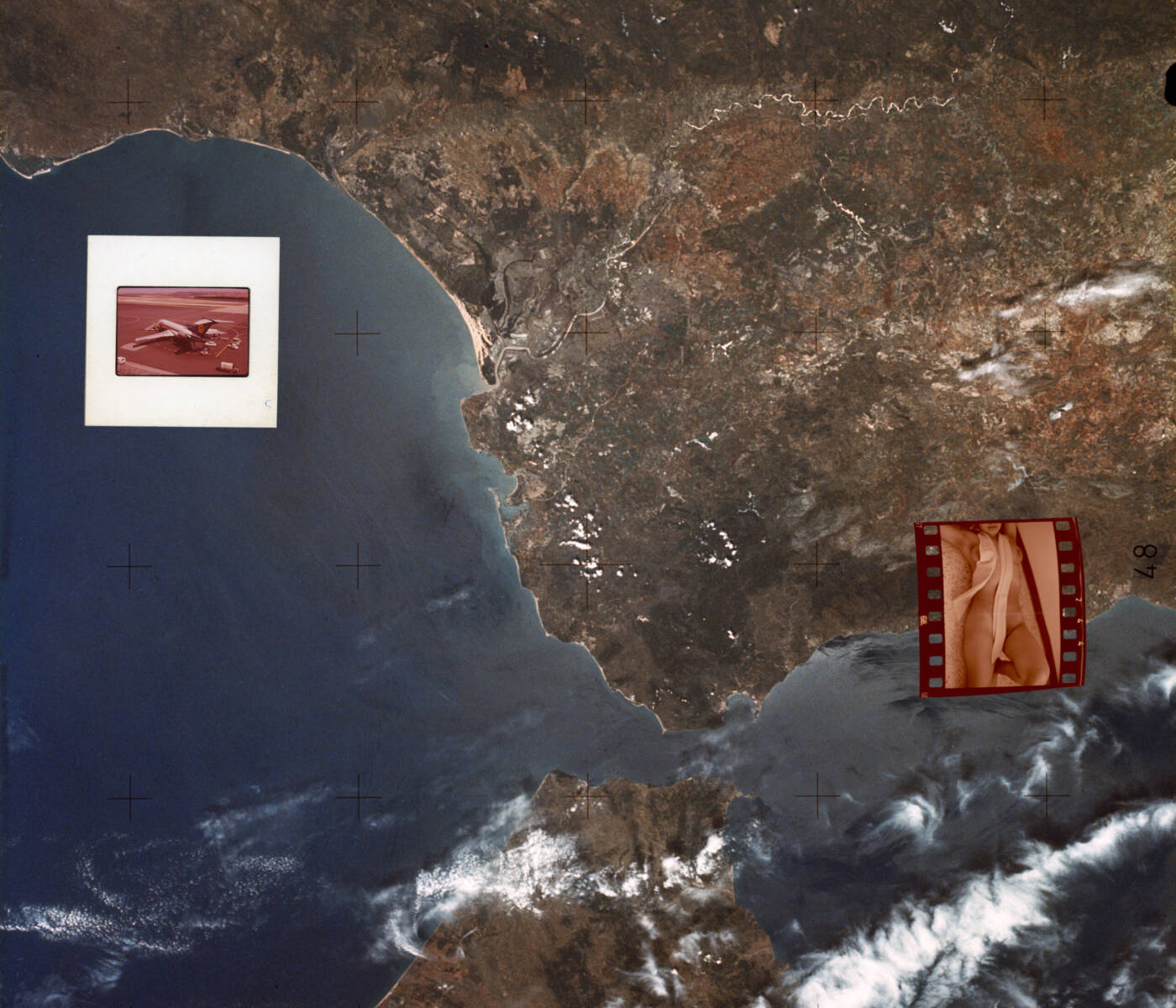

Captured from space by NASA on June 22, 1973, the Strait of Gibraltar stretches across continents and histories, a bridge between Africa and Europe. Below, Spain's coastline unfurls—from the Guadalquivir Delta and Seville to Málaga and the Costa del Sol, on a bright summer day, where mass tourism was already reshaping the landscape. Overlaying the image is a slide of a Lufthansa plane, a German commercial airline, at Almería airport, alongside a film negative of a nude young woman. The negative reflects a truth about Spain: a society moving faster than the nation trying to hold it back. While the regime clung to power, mass tourism exposed a country eager to break free. In places like Torremolinos, crowded beaches and nightlife sparked a growing divide between a strict government and a society embracing modern times. Barcelona, November 2024.

A line of tourist brochures unfolds the transformation of the Spanish coastline from the 1950s to the 1970s, from hundreds of thousands to tens of millions of foreign tourists. At the top is the Comunidad Valenciana; at the bottom is Catalonia. Coastlines caught in the frenetic rush of the Spain is different. What began as a monochrome Spain, rooted in its rural culture, gradually transformed into a hardened coast, a concrete landscape, and apartment hotels. Amid the brochures, small relics of another era: photographic negatives, bus tickets, peseta coins, old light bulbs that can no longer handle today’s voltage (as if what was conceived then can’t bear today’s life), dried olive leaves and orange stamps evoking the Mediterranean landscape of Iberia. Today, ten and a half million tourists a year in the Comunitat Valenciana. That’s 196% of its local population. The apartments fill up, the beaches are packed, and the sea feels smaller. In Catalonia, with its sixteen million visitors, it reaches 198% of its own residents. More tourists than locals, like a sea of foreign faces that overflows each year, covers the sand, and then retreats, leaving the coast quiet and hardened as if nothing happened. And so, every summer, they return. But now, it’s not just for summer. The line between spring and autumn blurs yearly, and Spain remains the world’s resort. Coastal towns once quiet in the off-season fill with ‘permanent vacationers’—seasonal residents who buy homes, settle in, and turn temporary stays into something closer to permanence. The coastline stretches further each season, inching toward a landscape increasingly parched, a nation edging into desertification. Cadaqués (Costa Brava), shown in the image, represents a deliberate departure from the norm. While Spain's coastline gave way to concrete towers and endless developments, this small town set strict limits. No high-rises, no sprawling hotels. Decades later, the result is clear: a Mediterranean village that held onto what others let slip away. It’s not perfect, but it’s a quiet defiance against a tide that reshaped the rest. Barcelona, November 2024.

The ancient holm oak in El Valle Almanzora, recognized as Andalusia's largest tree, has witnessed centuries of history but now faces a dire future due to the impacts of desertification. Since 2021, its grand stature has been artificially supported, employing bracing to counteract the accelerating impacts of climate change. Almería's rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall contribute to severe water stress, challenging the tree's survival while diseases and pests exploit its weakened defenses. Valle del Almanzora, May 2024.

An old real estate advertisement displayed in a Benidorm shop window. Its faded image of sunlit beaches and orderly developments reflects a coastline reimagined for mass tourism, now operating as a functional monument to past and present ambitions. Through the lens of this storefront, a scene amid the flow of pedestrians along today’s promenade. Benidorm, September 2024.

In the mountains of Alcover, the dynamite blast signals ongoing limestone extraction for Spain's construction industry. This quarry in southern Catalonia is just one piece of the bigger picture, where high demand often outweighs environmental concerns. Despite efforts by companies to reduce their environmental footprint, the impacts of mining continue to scar the landscape. This reflects the need for more sustainable construction practices to balance growth with environmental care better. Alcover, March 2021.

Eugenio Merino’s silicon representation of Franco, a portrait of Spain’s past. Even more than four decades after his death, Franco’s shadow continues to pervade Spanish society, inciting fervent debates and controversies. The 2016 Barcelona exhibition ‘Franco, Victòria, República’ manifested Spain’s ongoing struggle to reconcile with its contentious history, evidencing its perpetual dialogue with its past. While many physical statues of Franco have been dismantled, his symbolic presence persists. Streets and buildings bearing names tied to his dictatorship continue to fuel controversy. His influence extends beyond politics, etching deep into Spain’s societal fabric. Barcelona, October 2016.